The Automat Is a Guide to the Wonders of Mid-Twentieth-Century Urbanism

Lisa Hurwitz’s ode to the Horn & Hardart restaurants—featuring Mel Brooks, Elliott Gould, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg—depicts cheap dining as a theatrical experience.

When Hurwitz questions the architectural dealer Steve Stollman (who collects the chain’s furnishings) about the “idealism” of Horn & Hardart, Stollman responds, “I think the idealism was infused into the lives of the people who experienced the Automat.” I think he’s right—and that, like any ideal, like any original idea, its inspirational power is out of control.

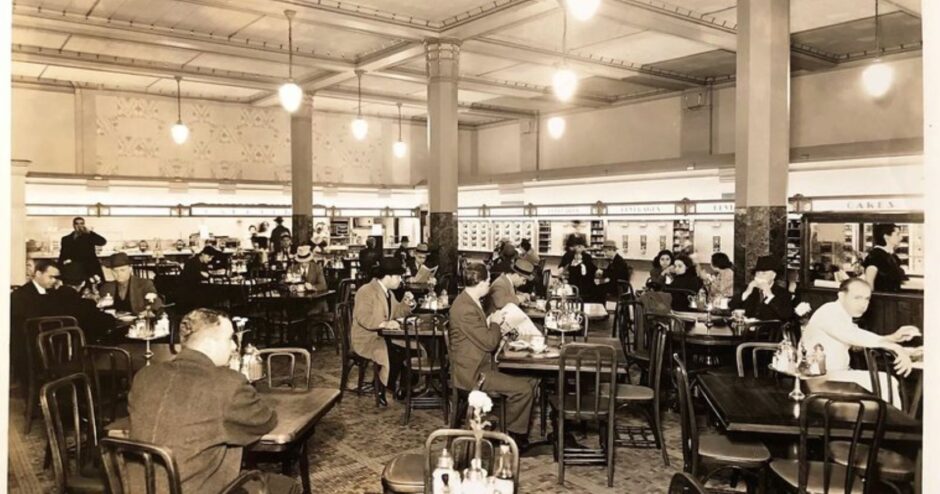

The high style of movies such as “The French Dispatch,” “Zola,” and “Strawberry Mansion” is more than a matter of décor; their performances are stylized because style is as much a way of life as it is a visual delight. In Lisa Hurwitz’s new documentary, “The Automat,” which opens today at Film Forum, the equation is surprisingly reversed: it spotlights the enduring power of everyday, street-level style. The subject is a piece of New York (and Philadelphia) nostalgia: the once ubiquitous self-service Horn & Hardart restaurants that, as Hurwitz’s film makes clear, were as noteworthy for their décor and their social life as for their inexpensive but tasty food. (I speak from a personal childhood memory.) The film, which uses a conventional round of interviews with people whose lives intersected with the restaurants and a tangy selection of historical documents and archival footage, shows that the style in question was more than a matter of marketing; it was, as in the work of artists, the embodiment of an idea—even of an ideal.

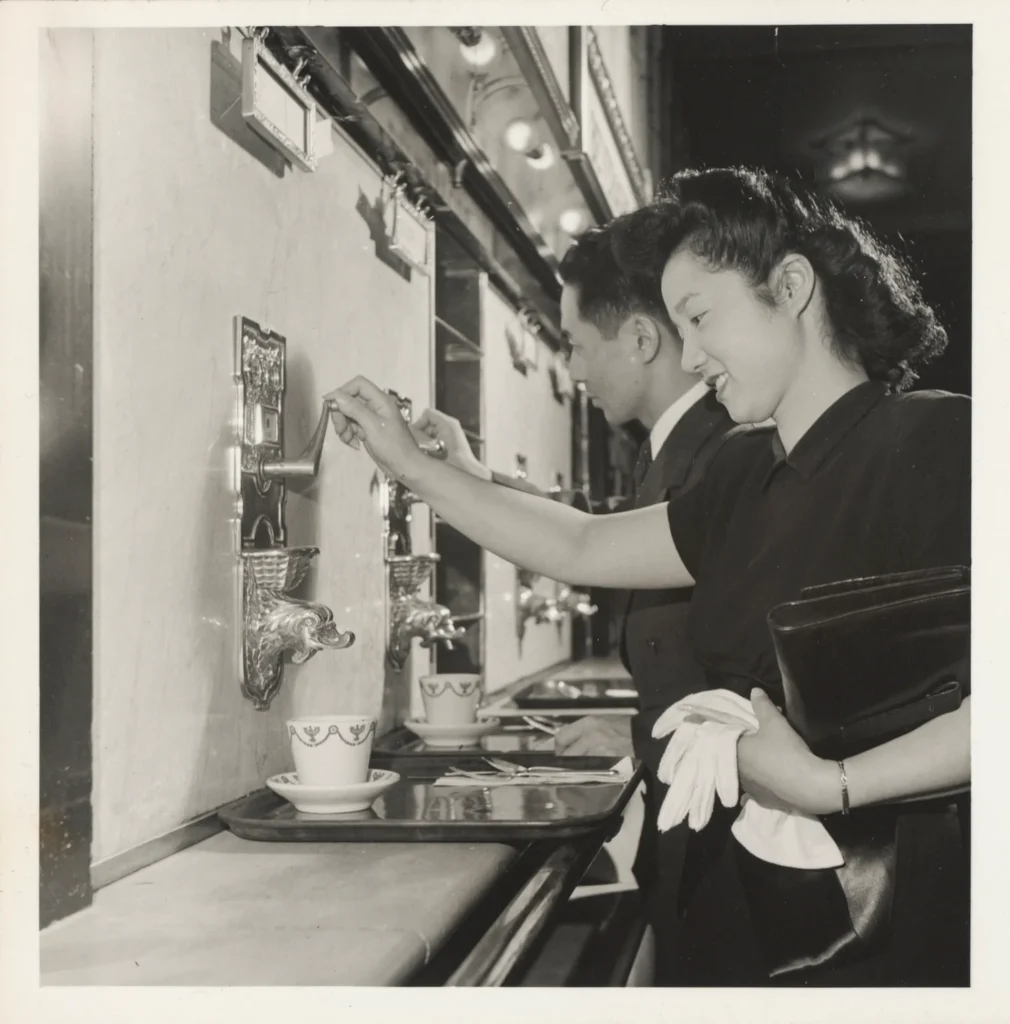

Hurwitz’s prime guide into the elusive wonders of mid-twentieth-century urbanism is none other than Mel Brooks, born in 1926, who grew up in Williamsburg and went with his brothers to Manhattan (which, he emphasizes, they all called New York, as did my Brooklynite ancestors) to eat, cheaply but well, at a Horn & Hardart Automat. Discussing a brief article by Brooks nearly a decade ago, I exhorted him to write a memoir, because his power of memory, with its profusion of vivid details, is inherently literary, and his recollections in “The Automat” make him no mere tour guide along memory lane but a veritable Virgil from a vanished world of ordinary graces. (I took particular pleasure in his mention of the booth where a clerk changed dollar bills into nickels, through a cutout in a window, passing the coins through a counter where “the wood was very smooth” from constant use.)

The delight of “The Automat,” which also features twenty-one other interview subjects from many walks of life and connections to the restaurant chain, is its blend of social and intellectual history with its anecdotal history—its evocation of the links between intention, practice, and experience; its depiction of a largely lost aesthetic of daily life. Hurwitz sketches the restaurant’s nineteenth-century roots: the desire of the Philadelphia-born Joseph Horn to open his restaurant, and the dream of a German immigrant in New Orleans named Frank Hardart to export that city’s style of coffee. Inspired by mechanized German self-service restaurants, they opened their first Automat in Philadelphia in 1902, and their first in New York ten years later. They soon opened more, in both cities: Horn stayed in Philadelphia and ran the restaurants there; Hardart (and, after his death, his sons) ran the ones in New York. The film links the rapid expansion and success of both chains to the two cities’ economic boom (a growing workforce meant more people eating meals away from home and near offices) and to the rise of immigrant populations, who could eat in self-service restaurants without having to order in English.